In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm

Raft is a consensus algorithm, meaning that it is designed to facilitate a set of computers agreeing on a state of the world (more on exactly how the state of the world is represented later), even when communications between the computers in the set are interrupted (say for example, by someone accidentally unplugging a network cable that connects some of the nodes to the majority).

The problem of reliably storing a state of the world across many computers, keeping the state in sync, and scaling this functionality is required in a number of modern systems - for example, Kubernetes stores all cluster data in etcd, a key-value store library that uses Raft under the hood.

Why Raft ?

Raft is an algorithm designed to help computers synchronize state through a process called consensus, although it was not the first system designed to do so.

A main difference between Raft and previous consensus algorithms was the desire to optimize the design with simplicity in mind - a trait that the authors thought was missing from existing research.

Raft is a consensus algorithm for managing a replicated log. It produces a result equivalent to (multi-)Paxos, and it is as efficient as Paxos, but its structure is different from Paxos; this makes Raft more understandable thanPaxos and also provides a better foundation for build-ing practical systems.

Raft separates the key elements of consensus, such as leader election, log replication, and safety, and it enforces a stronger degree of coherency to reduce the number ofstates that must be considered.

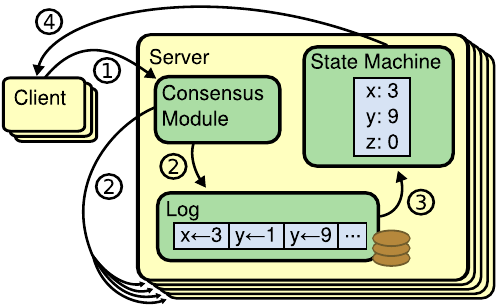

Fig1: Overview of core protocol

How does Raft work?

- The purpose of the Raft algorithm is to replicate a state of the world across a cluster of computers. Rather than sending single messages that contain the complete state of the world, Raft consensus involves a log of incremental changes, represented internally as an array of commands. A key value store can be used as a more concrete example of representing the state of world with in this way the current state of the world in a KV store contains the keys and values for those keys, but each put, or delete is a single change that leads to that state. These individual changes can be stored in an append-only log format.

- Raft peers communicate using well-defined messages. There are several defined in the original paper, but the two essential ones are:

- RequestVote: a message used by Raft to elect a peer that coordinates updating the state of the world.

- AppendEntries: a message used by Raft to allow peers to communicate about changes to the state of the world.

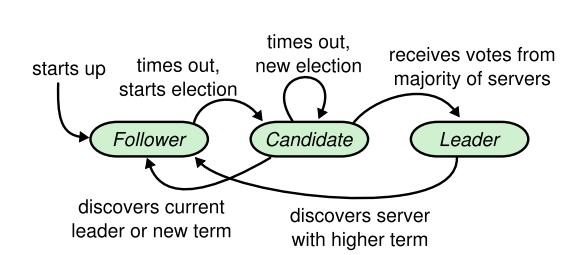

- Members of a Raft cluster are called peers and can be in one of three states:

- Leader: the node that coordinates other nodes in the cluster to update their state. All changes to the state of the world flow through the Leader.

- Candidate: the node is vying to become a leader

- Follower: the node is receiving instructions about how to update its state from a leader

- A Leader manages updates to the state of the world by taking two types of actions: committing and applying. The leader commits to an index in its log (called a commitIndex) once a majority of the nodes in the network have acknowledged that they’ve also stored the entry successfully. When a node moves its commitIndex forward in the log (the commitIndex can only move forward, never backward!), it applies (processes) entries in the log up to where it is committed. The ideas of committing and applying ensure that a Leader doesn’t update its state of the world until it is guaranteed that the log that led to that state is impossible to change.

With that context, we can start breaking Raft down into more concrete sections that try to answer questions about the protocol:

- Leaders and leader election covers how updates to a Raft cluster’s state are coordinated: Which computer is coordinating changes to the state of the world, how does this computer coordinate with other computers in the Raft cluster, and for how long does the computer coordinate?

- Raft logs and replication covers the mechanism of state being replicated: How does the state of the world get propagated to other computers in the cluster? How do other computers get new information about the state of the world if they were disconnected, but are now back online (someone unplugged the computer’s ethernet cable)?

- Safety covers how Raft guards against edge cases that could corrupt the state of the world: How do we make sure that a computer with an old state of the world does not accidentally overwrite another computer’s updated state of the world?

Leaders and leader election

The Raft protocol requires a single node (called the Leader) to direct other nodes on how they should change their respective states of the world. There can only be one leader at a time - Raft maintains a representation of time called a term. This term only changes in special situations, like when a node attempts to become a Leader. When a Raft cluster starts, there are no leaders and one needs to be chosen through a process called Leader Election before the cluster can start responding to requests.

How does the leader election process work?

A node starts the leader election process by designating itself to be a Candidate, incrementing its term, voting for itself, and requesting the votes of other nodes in the Raft cluster using RequestVote.

There are a few ways that a node can exit Candidate state:

- If the Candidate node receives a majority of votes within some configurable time period of the election starting, it becomes the leader.

- If the Candidate node doesn’t receive a majority of votes within some configurable time period of the election starting (and it hasn’t heard from another leader, as in the case below), the node restarts the election (including incrementing its term and and sending out RequestVote communications again).

- If the Candidate (Node A) hears from a different peer (Node B) who claims to be Leader for a term greater than or equal to the term that Node A is on, Node A stops its election, sets its term to Node B’s, enters the Follower state, and begins listening for updates from the Leader.

Once a node becomes a Leader, it begins sending communications in the form of AppendEntries messages to all other peers, and will continue trying to do so unless it hears about a different Leader with a higher term .

To allow Raft to recover from a Leader failing (maybe because of an ethernet unplugging scenario), an up to date Follower can kick off an election.

Fig2: Raft State transitions

Raft logs and replication

What is an AppendEntries request and what information does it contain?

As mentioned above, Leader nodes periodically send AppendEntries messages to Follower nodes to let the Followers know that there is still an active Leader. These AppendEntries calls also serve the purpose of helping to update out of date Followers with correct data to store in their logs. The information that the leader supplies in the calls is as follows:

- The Leader’s current term - as mentioned in the Leaders and leader election section, if a node is a Candidate or a Leader, hearing about a new or existing leader might require the node to take some action (like giving up on an election or stepping down as a Leader).

- Log entries (represented as an array) that the Leader wants to propagate to peers, along with data about the Leader’s log that will help the Follower make a decision about what to do with the new entries. In particular, the Leader sends data about the log entry that immediately preceded the entries it is sending. Because the data pertains to the previous log entry, the names of the variables are previousLogIndex and previousLogTerm.

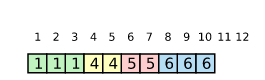

Fig3: Leader log

For an example of how these variables are assigned, consider a Leader’s log as shown in the margin. If the leader wanted to update the follower with entries that are in positions 9 through 10, it would include those in the log entries section of the AppendEntries call, setting previousLogIndex to 8 and previousLogTerm to 6.

- The Leader’s commitIndex: this is where the idea of committing disscussed in the earlier part comes into play.

What happens when a peer receives an AppendEntries request?

Once a peer receives an AppendEntries request from a leader, it evaluates whether it will need to update its state, then responds with its current term as well as whether it successfully processed the request:

- If the receiving node has a greater term than the sending node, the receiving node ignores the AppendEntries request and immediately communicates to the sending node that the request failed. This has the effect of causing the sending node to step down as a leader. A situation where this could arise is when a Leader is disconnected from the network, a new election succeeds (with a new term and Leader), then the old Leader is reconnected. Because Raft only allows one leader at a time, the old one should step down.

- If the receiving node has an equal term as the sending node, a few conditions need to be evaluated: Firstly, if the receiving node is not a Follower, it should immediately transition to being one. This behavior serves to notify candidates for the term that a Leader has been elected, as well as guarding against the existence of two Leaders. Hitting this condition does not cause the AppendEntries request to return.

- Once it has been checked that the receiving and sending nodes have the same term, we need to make sure that their logs match. This check is performed by looking at the previousLogIndex and previousLogTerm of the sending node and comparing to the receiving node’s log. As part of performing this check, a few scenarios arise.

- In the match case, the previousLogIndex and previousLogTerm of the sending node match the entry in the receiving node’s log, meaning that everything is up to date! If this is true, the receiving node can add the received entries to its log. The receiving node also checks whether the Leader has a newer commit index (meaning that the receiving node is able to update its commit index and apply messages that will affect its state)

- If the log for a Follower is not up to date, the Leader will keep decrementing the previousLogIndex for the Follower and keep retrying the request until the logs match (the match case above is true) or it has been determined that all entries in the Follower need to be replace

- Once it has been checked that the receiving and sending nodes have the same term, we need to make sure that their logs match. This check is performed by looking at the previousLogIndex and previousLogTerm of the sending node and comparing to the receiving node’s log. As part of performing this check, a few scenarios arise.

Raft Safety

At the core of Raft are guarantees about safety that make sure that data in the log isn’t corrupted or lost. For example, imagine that a Leader starts coordinating changes to the log, does so successfully, then goes offline. While the existing Leader is offline, a new Leader is elected and the system continues updating the log. If the old Leader were to come back online, how can we make sure that it isn’t able to rewind the system’s log?

To account for this situation (and all of the edge cases that can occur in distributed systems), Raft aims to implement several ideas around Safety. A few of these we’ve already touched on (descriptions are from Figure 3 of the original Raft paper):

- Election Safety: “There can at most be one leader at a time.”

- Leader Append-Only: “a leader never overwrites or deletes entries in its log; it only appends new entries.” The leader never mutates it’s internal logs.

- Log Matching: “if two logs contain an entry with the same index and term, then the logs are identical in all entries up through the given index.” If the leader doesn’t have logs that match followers, the leader will rewind the follower’s log entries, then send over the correct data.

The other important ideas around Raft Safety are:

- Leader Completeness: “if a log entry is committed in a given term, then that entry will be present in the logs of the leaders for all higher-numbered terms”. The gist of this principle is to ensure that a leader has all log entries that should be stored permanently (committed) by the system. To make the idea of Leader Completeness concrete, imagine a situation where a key-value store performs a put and then a delete - if the put operation was replicated, but the delete happened in a higher term and is not in the log of the leader, the state of the world will be incorrect, as the delete will not be processed. To ensure that leaders aren’t elected with stale logs, a node that receives a RequestVote must check that the sender has a log where the last entry is of a greater term or of the same term and of a higher index. If the receiver determines that neither of those conditions is true, then it rejects the request.

- State Machine Safety: “if a server has applied a log entry at a given index to its state machine, no other server will ever apply a different log entry for the same index.” The gist of this principle is to ensure that a leader applies entries from its log in the correct order. To make the idea of State Machine Safety concrete, imagine a situation where a key-value store performs a put and then a delete (both of which are stored in individual log entries). If the put operation was applied, then the delete operation was applied, every other node must perform the same sequence of applications. A more detailed explanation of the proof is available in the Raft paper.